News

Is the Army Really Ready to Defend Ukraine as Spending Warnings Mount

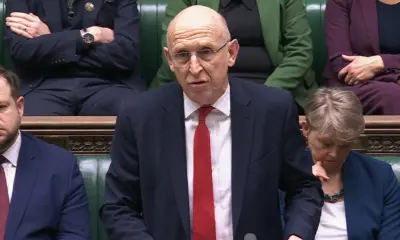

Questions over whether Western militaries are truly prepared to defend Ukraine are growing louder, as former UK defence secretary Ben Wallace warns that inadequate defence spending could undermine any future coalition tasked with deterring renewed Russian aggression.

Wallace has raised concerns that while political rhetoric around supporting Ukraine remains strong, the practical reality on the ground tells a more troubling story. He argues that years of underinvestment have hollowed out key military capabilities, leaving armies stretched, under equipped and struggling to sustain high intensity operations over long periods.

The debate comes amid ongoing discussions among European allies about security guarantees for Ukraine once the current phase of the war ends. Proposals have included the deployment of multinational forces, training missions and long term deterrence arrangements. Wallace cautions that without serious investment, such commitments risk becoming symbolic gestures rather than credible security measures.

At the heart of the concern is readiness. Modern warfare in Ukraine has exposed the scale of resources required to sustain combat, from artillery shells and air defence systems to logistics, maintenance and trained personnel. Wallace points out that many European armies, including the British Army, have reduced troop numbers and stockpiles over the past decade, assuming large scale land wars were unlikely.

He argues that this assumption has been decisively overturned. The conflict has shown that industrial capacity, resilience and mass still matter, even in an age of advanced technology. Armies must be able not only to deploy forces but to replace losses, rotate units and maintain pressure over months or years.

Critics of current defence policies say spending increases announced by governments often fall short of what is required. Inflation, rising equipment costs and delays in procurement have eroded the real value of defence budgets. In some cases, funding is absorbed by maintaining existing capabilities rather than expanding or modernising them.

The concept of a coalition of the willing has been floated as a way to provide Ukraine with reassurance without formal NATO membership. Wallace warns that such a coalition would face immediate credibility tests. Any force deployed would need robust air defence, intelligence, logistics and clear rules of engagement. Without these, it could be vulnerable and ineffective.

There is also the question of public and political endurance. Wallace notes that sustaining a meaningful military presence abroad requires long term commitment that goes beyond short term political cycles. If funding and manpower are not secured for the long haul, adversaries may simply wait for resolve to weaken.

Supporters of current policy argue that Western militaries are adapting rapidly. Training programmes have expanded, defence industries are ramping up production and coordination among allies has improved. They say deterrence does not require matching Russia troop for troop but demonstrating unity, capability and the willingness to respond decisively.

However, Wallace remains sceptical that adaptation is happening fast enough. He has urged governments to be honest with their publics about the costs of security, arguing that deterrence is cheaper than war but still demands real investment.

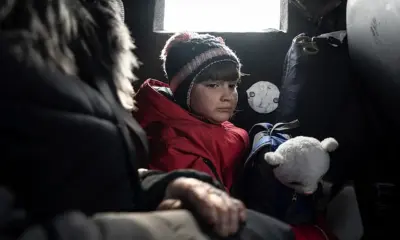

For Ukraine, the stakes could not be higher. A security guarantee that lacks substance risks inviting further aggression rather than preventing it. For Europe, the issue goes beyond one country, touching on the credibility of collective defence in an increasingly unstable world.

As debates continue in capitals across the continent, Wallace’s warning serves as a reminder that defending peace requires more than statements of intent. Without sustained spending, industrial capacity and political will, any coalition may find itself unprepared when it matters most.