News

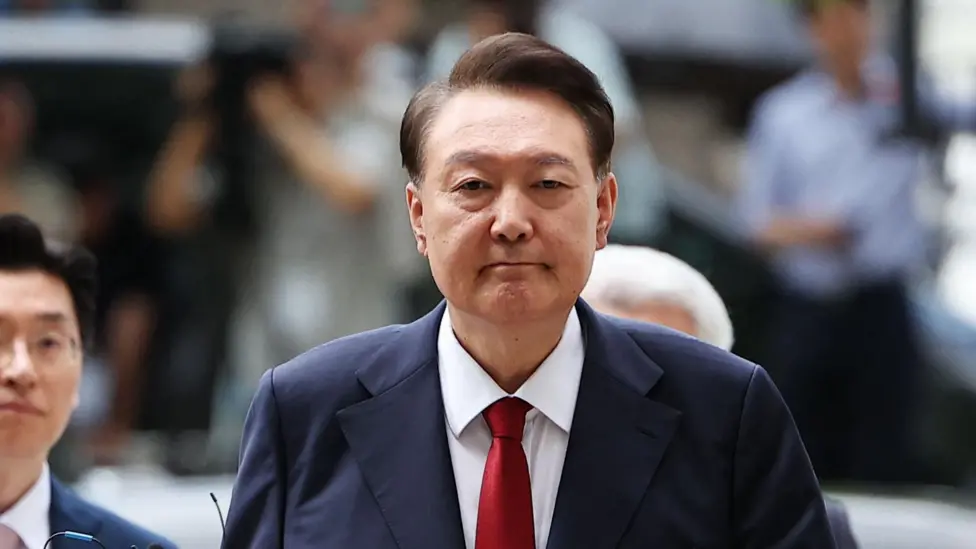

South Korean Prosecutors Seek Death Sentence for Former President Yoon Over Martial Law Bid

South Korean prosecutors have asked a court to consider the death penalty for former president Yoon Suk Yeol if he is found guilty over his failed attempt to impose martial law, a dramatic episode that plunged the country into political crisis late last year. The request was made during closing arguments in Yoon’s trial at a court in Seoul, bringing one of the most extraordinary cases in South Korea’s modern political history closer to a verdict.

Yoon is accused of being the ringleader of an insurrection following his decision in December 2024 to declare martial law, a move that lasted only a few hours but sent shockwaves through the nation. Prosecutors argued that the attempt represented a direct assault on constitutional order and democratic governance, regardless of how briefly it was in force. They said the severity of the charge justified the harshest possible punishment under South Korean law.

According to the prosecution, Yoon abused his presidential authority by attempting to mobilise military power for political purposes. They told the court that even though the declaration was quickly reversed, the act itself demonstrated intent to override civilian rule and suppress political opposition. Prosecutors stressed that South Korea’s history of authoritarian rule made the incident particularly grave, given the country’s hard-won transition to democracy.

The former president was impeached by parliament shortly after the incident and later detained to stand trial. Lawmakers across party lines described the declaration as unconstitutional, while mass protests erupted in Seoul and other cities, with demonstrators demanding accountability and the protection of democratic institutions. The episode marked a dramatic fall for Yoon, who had campaigned on promises of strong leadership and rule of law.

Yoon has consistently denied the charges. In his defence, he argued that the martial law declaration was intended as a symbolic gesture rather than a genuine attempt to seize power. His legal team told the court that the move was designed to draw public attention to what Yoon described as obstruction and wrongdoing by the opposition party, not to dismantle democracy. They said there was no plan to carry out widespread arrests or suspend constitutional rights.

South Korea technically retains the death penalty, but executions have not been carried out for decades, effectively placing the country under a moratorium. Even so, the prosecution’s request is symbolically significant, reflecting the seriousness with which the state views the charges. Legal experts say it is rare for prosecutors to seek such a sentence against a former head of state, underscoring how unprecedented the case is.

The trial has sparked intense debate within South Korea about presidential power, accountability, and the limits of executive authority. Supporters of Yoon argue that the prosecution is politically motivated and warn that criminalising controversial political decisions could set a dangerous precedent. Critics counter that failing to hold a former president accountable for such actions would weaken democratic safeguards.

Public opinion remains deeply divided. While many South Koreans view the martial law attempt as an alarming overreach, others believe the response has been excessive. The case has reopened old wounds related to the country’s authoritarian past, when military rule and emergency powers were used to silence dissent.

The court is expected to deliver its verdict in the coming weeks. Whatever the outcome, the trial of Yoon Suk Yeol is likely to have lasting implications for South Korea’s political system, shaping how future leaders interpret their powers and how firmly democratic norms are defended.